Ningyo-yaki and Chiropractic at Suehiro Dori Sekkotsuin

Published: July 6, 2020

Koto-ku is home to many fascinating people but none have the remarkable combination of occupations as Mr. Koji Kobayashi. Based on the Suehiro Dori shopping street in the east of the ward near the Arakawa River, Mr. Kobayashi combines a family tradition of making ningyo-yaki, small sweet cakes baked in iron molds, with another career as a chiropractor and osteopath. On a recent afternoon, we dropped in to meet a man who wears two wildly disparate hats, and his charming nutritional adviser, Ms. Junko Ryukai.

“My father made ningyo-yaki for around 50 years. He started in Morishita then we moved here about 45 years ago. Higashisuna soul food, people call them,” explained Mr. Kobayashi. “His ningyo-yaki became popular and he received many orders from supermarkets and other stores to supply ningyo-yaki for their own brand labels. Many people have eaten our products without knowing where they actually came from. At peak production, there were several people working here, making huge numbers every day.”

While the precise origins of ningyo-yaki are unclear, it’s generally accepted they first appeared in the Nihonbashi-Ningyocho area of central Tokyo and are smaller versions of the older Imagawa-yaki and the later Taiyaki. Ningyo-yaki are small and soft, while Imagawa-yaki are larger, round, and crisper. Taiyaki, baked in sea-bream shaped molds, are larger still and very crisp. Ningyo-yaki at Kotoya contain only flour, eggs, and sugar water. Mr. Kobayashi cleans out the molds, fires up the gas heaters, and checks the temperature.

“These days it’s more of a hobby than a business,” explains Mr. Kobayashi. “I usually make up a few batches at lunch time for local kids and families to pick up for an afternoon snack on their way home from school. If it’s raining, I won’t make them. We lost my father a couple of years ago, so I wanted to maintain the family tradition and continue to use his molds.” He makes two kinds, a plain version and one with sweet red bean paste (anko).

Prices are extremely reasonable at Kotoya: ningyo-yaki with bean paste are seven for 200 yen, eleven for 300 yen, or twenty for 500 yen. Without bean paste, they’re 200 yen for 10, 300 yen for 16, 400 yen for 22, or 500 yen for 30.

We ate them piping hot, straight from the molds and they were excellent; slightly moist, not too sweet and with a nice springy texture (mochi mochi). It’s easy to understand why they have been so popular for over 50 years.

According to Mr. Kobayashi, some hardcore ningyo-yaki fans loved the crispy overspill so much that they asked him to make a biscuit version. He spreads the batter on the spaces between the molds in a figure eight pattern, then closes the molds for a few seconds.

He deftly rolls up the cooked batter, which has now become a crunchy biscuit. One can imagine these would be very nice with some vanilla ice cream in summer.

The obvious question is how did a traditional Japanese confectionery maker come to be a chiropractor-osteopath? “Well, I grew up helping my family in the ningyo-yaki and snack business here, then became a regular company employee later on. My father and I realised that the Higashisuna shopping street trade and the general ningyo-yaki business were in decline, so I retrained as a chiropractor and osteopath,” he explained.

“When I qualified in 1995, we remodeled the front of the building into a clinic space. Many of my customers have small children so it’s convenient for them to have a space to play while their mothers have a session.”

“I studied under a globally-renowned chiropractic instructor named Hirotaka Miyano. He’s an expert in both the Sacro-Occipital Technique developed by the American chiropractor and osteopath Major DeJarnette and Cerebrospinal Fluid Cranial practice, both of which I also use. Basically speaking, I developed my own style over the years, like most other chiropractors. It’s a very difficult skill to master and, like calligraphy for example, it takes years to learn,” Mr. Kobayashi explains, looking totally different in his loose black chiropractic uniform.

The chiropractic table stands upright from the base so patients can simply step on before it is returned to the horizontal. His touch is very gentle, none of the dramatic twisting and pressing sometimes associated with chiropractic or osteopathy.

“People don’t need hours of expensive treatment,” he says. “Just ten minutes a day is enough for most people. The human body is rather like a battery; we can charge it up every day but the underlying condition of the battery is the key point.”

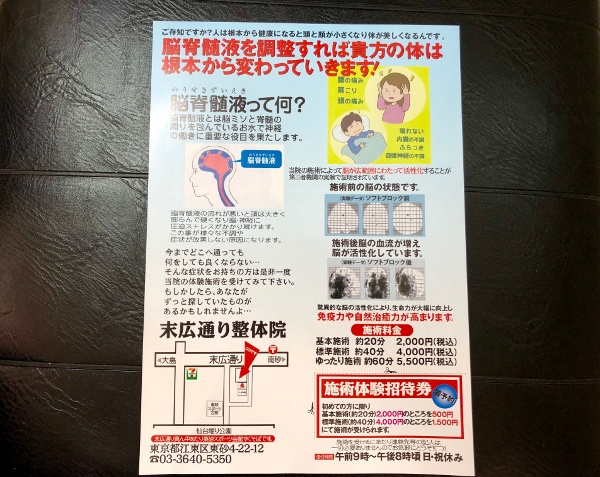

Mr. Kobayashi charges extremely reasonable prices for his services: a basic 20-minute session is 2,000 yen, 40 minutes is 4,000 yen, and 60 minutes is 5,500 yen including tax. Customers can use National Health Insurance (kokumin kenko hoken). Trial sessions are available too: just 500 yen for a 20-minute trial or 1,500 yen for a 40-minute session. “This style of chiropractic is designed to increase vitality, prevent hardening of the muscles and improve the autonomic nervous system together with the spinal nerve cells,” he says.

I enjoyed a trial session, which involved some head manipulation, spinal straightening, gentle pushing, light massage, and mild squeezing of my back and legs. Mr. Kobayashi also makes use of wedge-shaped pads slipped under the hips to aid in realigning the spine. It felt very comfortable indeed, a warm and pleasant experience. On returning to the upright position I felt really good, as if I was walking on air, and that feeling remained for quite some time.

While daytime customers are mainly local residents and seniors, many working people take a session in the evening. As the afternoon wore on Mr. Kobayashi’s phone rang frequently with customers wanting to make an appointment. If you’re in the area why not call Mr. Kobayashi and make an appointment for a trial session. Not only can visitors meet a truly unique person, they can enjoy the traditional flavour of a great Tokyo confectionery and have a fantastic chiropractic session to improve their mental and physical health.

Story and photographs by Stephen Spencer