Superior Soba and Tasty Tempura at Botancho Asanoya!

Published: March 11, 2020

Botancho Asanoya is a soba restaurant in the Botancho area of Koto-ku, a four-minute walk from Monzen-nakacho station. Initially opened in 1889, it has been rebuilt twice on exactly the same spot, first following the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake and the wartime bombing of east Tokyo, and is currently run by fourth generation proprietor Mr. Akihiro Yamamoto. On a warm spring afternoon, I dropped in to talk noodles with the affable Mr. Yamamoto and his charming wife.

Fronting on the busy Kiyosumi Street, Asanoya is unmissable thanks to its bright yellow noren curtain, cartoons featuring the cats Hana and Taro and the shocking pink peonies, from which Botancho received its name.

The text on the right indicates that Asanoya is a member of the local chapter of the Tokyo Noodle Makers Association and serves Tokyo ni-hachi soba. Ni-hachi (literally two-eight) is soba made with 80% soba flour and 20% wheat flour. Soba flour is famously brittle so wheat flour is added as a binder, with eighty-twenty the popular ratio. 90% soba is available but it’s rare. The soba flour used at Asanoya is stone-ground autumn flour from the Hitachi region of Ibaraki Prefecture, autumn being the premier season for soba.

Asanoya is designed in the grand tradition of soba restaurants: solid wooden tables and chairs with a tiled stone floor. The atmosphere is pleasantly relaxed; a radio plays quietly as a couple of businessmen and some local ladies enjoy a late lunch.

Mr. Yamamoto kindly offers to make a batch of soba. He brings out his kibachi, the large lacquered kneading bowl used by soba makers, sieves a bag of flour mix into it and adds water. “We add about 80% of the water at first and the rest little by little as we slowly knead the soba,” he explains.

He slowly works the water into the flour, creating small nubbins of dough. “You’ve got to keep the dough slightly moist but not sloppy and firm, yet neither limp nor too hard. If the dough becomes too hard it won’t absorb the water. It wants to be slightly sticky too,” he adds. As he kneads the flour it releases a rich, earthy smell that fills the room.

After about ten minutes of kneading the nubbins suddenly form themselves into one ball which Mr. Yamamoto presses hard with the heel of his hand. “I make soba every day,” he explains. “It has to be made fresh and then eaten immediately after cooking or it dries out.”

The resulting ball is given a preliminary rolling with a small rolling pin before Mr. Yamamoto leads me down some steep stairs into the basement where the soba machine is located.

The dough is fed through the machine’s rollers a couple of times to produce the required thickness.

Before it’s fed through the machine once more and turned into the quite thin noodles served at Asanoya.

While all soba contains the same basic ingredients of buckwheat flour and wheat flour, the resulting noodles vary depending on the soba flour, the ratio of wheat flour used, the thickness of the noodles and the gluten content of the wheat flour. At Asanoya, Mr. Yamamoto serves a double decker with 100g grams of soba on each tray, “to avoid having a mountain of noodles on one large tray as they dry out quickly that way,” as he explains. A regular serving costs 800 yen, with an extra large at 1,150yen.

The noodles are great, nutty and toothsome with a delightful aroma. The dipping sauce has a rich savoury flavour, bursting with umami goodness that makes a wonderful combination. A little freshly grated wasabi and ginger, and some thinly sliced negi onions, extends the taste panorama even further.

All the most popular soba variations are available at Asanoya. The selection of deep-fried (tempura) items is extensive, taking in seasonal vegetables, shrimp, oysters, squid, clams, chicken, whitebait, whiting, conger eel and so on. The serving here contains shrimp, pumpkin, lotus root with nori (seaweed paper), green beans, okra, baby corn, and onion.

The plump shrimp was terrific, the outer tempura crisp and light, the meat sweet and juicy.

The onion was incredibly crisp, with a superb contrast between its sweetness and the savoury flavour of the tempura sauce.

Not only does Asanoya serve soba and tempura but also the thick wheat noodles called udon. According to Mr. Yamamoto, “It’s about 50-50 with soba and udon in winter but 90% soba in summer.” It’s understandable as stepping from the sweltering heat and blinding brightness of midsummer Tokyo into a discretely lit, cool soba restaurant for a chilled beer and a plate of cold zaru soba is one of the great pleasures the city has to offer.

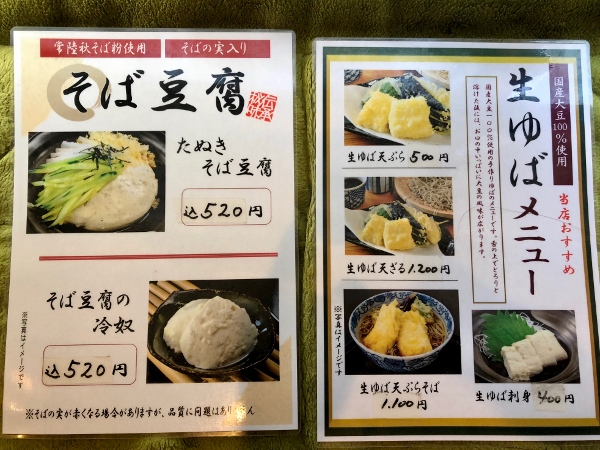

Also on the menu is a wide selection of small dishes (otsumami) to be eaten with sake. I was surprised to find yuba, a delicacy often associated with Kyoto and Nikko, both raw and as tempura. Both soba tofu and yuba tempura are available at very reasonable prices.

Made from the skins that form on the surface of soy milk when it is gently boiled in shallow pans, the yuba has the consistency of a soft Brie and a delicate, creamy flavour. Very nice indeed.

Mr. Yamamoto was also remarkably forthcoming on the ingredients of his sauces. For the regular sauce used with hot noodles he combines the fragrant frigate tuna shavings with the sweet and powerful mackerel shavings. Glutamine-rich kelp (kombu) from Hidaka in Hokkaido is the only other ingredient. There are no artificial additives of any kind. The cold dipping sauce (seiro) is the same but with the addition of bright red, thickly sliced, two-year matured bonito from Kagoshima.

The traditional oldtown area around Monzen-nakacho boasts a host of attractions, from museums, parks and gardens to ancient temples and shrines. If you’re visiting, or a local resident, and fancy trying the traditional taste of soba and tempura, Mr. Yamamoto is waiting for you!

Story and photographs by Stephen Spencer